Keep exploring

Find even more resources on aquatic food webs in our searchable resource database.

Aquatic food webs show how plants and animals are connected through feeding relationships. Tiny plants and algae get eaten by small animals, which in turn are eaten by larger animals, like fish and birds. Humans consume plants and animals from across the aquatic food web. Understanding these dynamic predator-prey relationships is key to supporting fish populations and maintaining healthy ecosystems so that we can all enjoy sustainable food supplies and a healthy environment.

Keep exploring

Find even more resources on aquatic food webs in our searchable resource database.

What is a food web?

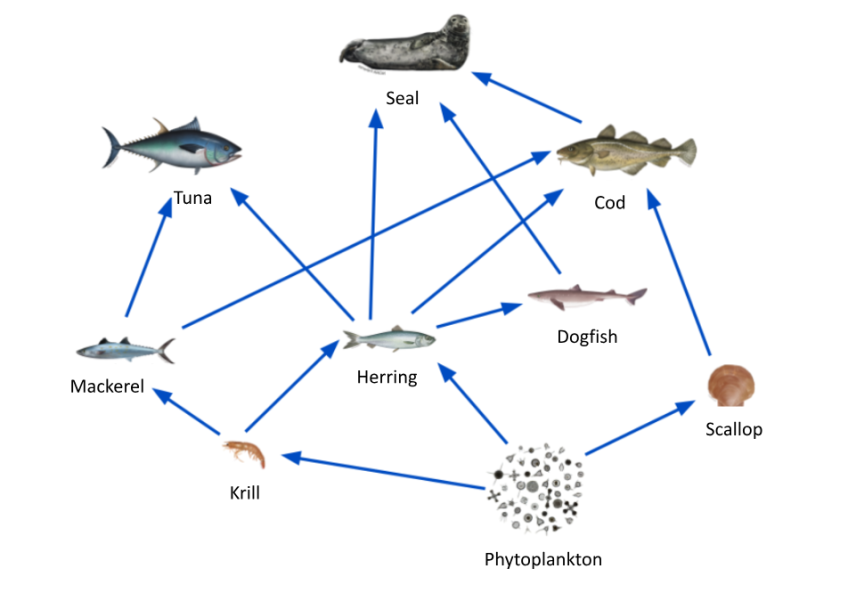

Food webs describe who eats whom in an ecosystem and therefore how energy flows through an ecosystem. All living things need energy to live and grow. Producers like plants make their own energy, while consumers eat other living things to get energy. The arrows in a food web show how energy flows from prey to predator.

Food webs help us understand how changes to ecosystems — for example, removing a top predator or adding nutrients — affect other species in the food web. These effects can be direct or indirect. Direct effects are when a change in the food web immediately impacts a species in the food web. Indirect effects are when direct effects “cascade,” or move throughout, the food web causing impacts to one or more connected species. A real life example of the direct and indirect effects of removing sea otters from Pacific kelp forests is provided in the Trophic cascade section below.

Ecological communities, or a group of organisms that live in the same area at the same time, tend to have complex interactions. Some animals eat plants and animals, while others are prey to many different predators within that community. Food webs are a great tool for describing these complicated interactions and can have many overlapping connections depending on the ecosystem.

A food web has multiple levels, called trophic levels. A trophic level defines where the organism fits into the food web:

- Producers like plants and algae are at the base of the food web.

- Primary consumers eat producers.

- Secondary consumers eat the primary consumers

- Tertiary consumers eat the secondary consumers.

In the example above, phytoplankton are a primary producer; krill, herring, and scallops are primary consumers; dogfish, cod, and mackerel are secondary consumers; and tuna and seals are tertiary consumers. Tuna and seals are at the top of the food web pictured here and have no natural predators apart from humans. Below, we describe how different types of organisms feed and how that connects to their trophic level in aquatic food webs.

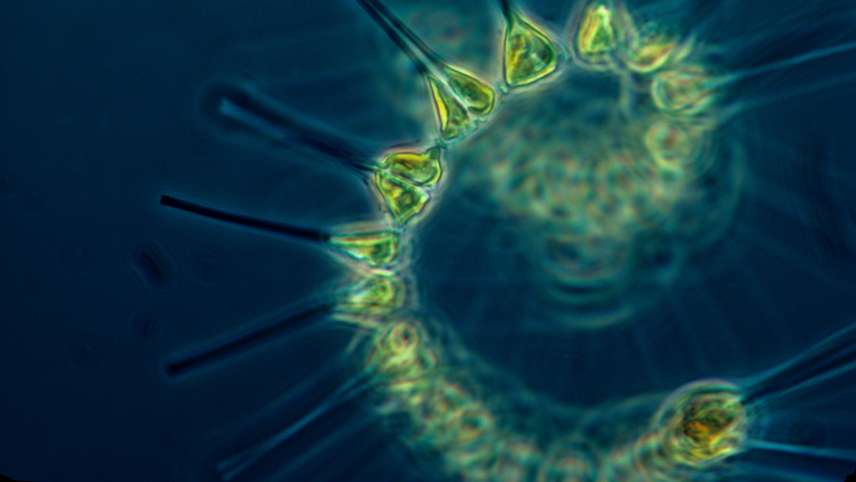

Producers

Primary producers — including bacteria, phytoplankton, and algae — form the lowest trophic level and the base of the aquatic food web. Primary producers do not need to eat. They make their own energy through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis. Photosynthesis is how plants use sunlight to make food for themselves. Chemosynthesis is used by some bacteria to turn chemicals released from hydrothermal vents, methane seeps, and other geological features into energy. Chemosynthesis does not require light.

Hollings scholar Seraina Rioult-Pedotti spent her summer looking at what Pacific halibut and black rockfish eat at the Kachemak Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Homer, Alaska. These sport fish play an important role in their environment as top predators. Seraina’s work helps fisheries managers figure out how many fish can be removed by recreational fishing without harming the whole ecosystem.

Consumers

Consumers are animals that cannot make their own food and need to eat other organisms for energy. Many consumers are opportunistic feeders, meaning they may eat anything within the food web and may be a combination of any of the types described here. Sometimes they even eat other organisms of the same species.

Herbivores

Herbivores are consumers that only eat plants or phytoplankton. All herbivores are primary consumers that eat from the base of the food chain. In aquatic food webs, herbivores come in all shapes and sizes. Herbivorous zooplankton are microscopic animals that graze on phytoplankton as they drift through the water. Other herbivores, including snails, fish, reptiles, and mammals, graze on algae growing on the seabed and filter feeders like oysters, mussels, tube worms, and sponges filter plankton out of the surrounding water.

Carnivores

Carnivores are animals that only eat other animals for energy and are either secondary or tertiary consumers. Carnivores that eat herbivores are secondary consumers because they are feeding on primary consumers. Carnivores that eat other carnivores are at least tertiary consumers because they feed on secondary consumers or consumers at a higher trophic level. All carnivores are considered predators, which have to attract or hunt their prey to eat. Apex predators, such as orcas or great white sharks, sit at the top of the food web with no predators of their own. These animals eat other consumers like seals, other sharks, and rays. In the marine environment, apex predators tend to travel large distances across the ocean throughout their lives while tracking prey.

Omnivores

Omnivores eat both plants and animals. While omnivores are usually secondary consumers, they can act as prey, predators, and sometimes scavengers. Some common aquatic omnivores include snails, sea turtles, zooplankton, and crabs.

Who cleans up the leftovers?

Scavengers eat dead or rotting remains of other animals and plants. Any scraps left behind by predators or organisms that died from natural causes can make a hearty meal for a scavenger. In the deep ocean, the remains of a single whale can feed many deep-water scavengers. Some organisms that eat dead or rotting remains are called detritivores instead of scavengers, but perform the same function in the environment. Anything remaining will be broken down by bacteria or fungi and recycled into nutrients for producers through decomposition.

NOAA Fisheries examines food web dynamics in the Northeast by studying predator-prey interactions. Scientists look at how the removal of prey populations affect fishery harvests and the surrounding ecosystem. The best way to do this is examine predator stomach contents on a regular basis and track the information in a Food Habits Database.

Trophic cascades: Ecosystem effects

Entire food webs can be changed by the population of one type of predator or prey within the food web. If there are limited numbers of one type of prey, a predator may switch to eating more of another prey species to meet their needs. This would be considered a direct effect on the food web. If a top predator is taken from the environment, the prey will be able to increase in numbers because they are not being eaten. This indirectly affects animals lower on the food chain that are then eaten more by the growing number of organisms. This is called a trophic cascade and it affects animals across multiple trophic levels.

A classic example of a trophic cascade is that of the sea otters, sea urchins, and kelp forests in the Pacific Ocean. Sea otters eat sea urchins, and sea urchins eat the kelp, making sea otters the top predator in this food chain. When sea otters were over hunted for their fur in the 1800s, the sea urchin population grew and ate all of the kelp. Without a remaining food source, all of the urchins died. Normally, the sea otters keep the sea urchin population from growing too quickly, which protects the kelp forest. Removing the top predator from the environment caused the ecosystem to collapse. Sea otter populations have grown since 1911, thanks to protections by laws such as the International Fur Seal Treaty, the Endangered Species Act, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act. There is still a lot of work to do to fully recover the large populations of the 1700s, but these protections and efforts to reintroduce sea otters offsite link to their native habitats continue.

Another Pacific coast top predator, the sunflower sea star, is facing a pandemic, dying from sea star wasting disease. Learn more about this modern day trophic cascade example, where again sea urchins pose a threat to kelp forests.

Many fisheries managers use ecosystem-based fisheries management, which is informed by ecosystem data. This includes how much prey is available for the fish they manage. Read about a technique that NOAA scientists use to quickly assess abundance of zooplankton, a major prey source at the base of the food web, and how fisheries managers use the data to make decisions.

Learn more about different aquatic ecosystems

Estuaries

An estuary is a body of water found where a river meets a larger body of water. Many estuaries are found where rivers meet the ocean. These ecosystems are some of the most productive in the world and are often dynamic, with some animals spending part of their lives in estuaries to reproduce before going back out to sea. Estuarine habitats support about 68 percent of the U.S. commercial fish catch and 80 percent of recreational catch, making it essential to understand the changing food web and how humans can affect it through fishing. Large lakes, including the Great Lakes, have estuaries, too. These unique estuaries are semi-enclosed areas where rivers and streams mix with the freshwater of the Great Lakes. The Great Lake estuaries are different from a traditional estuary where fresh and saltwater mix, instead formed by two freshwater ecosystems blending together as river meets lake. Great Lake estuaries like that in Lake Superior support a range of native fish species creating passage to rivers and acting as a nursery ground.

Learn about estuarine food webs.

Open ocean

The open ocean, or pelagic ecosystem, is extensive and includes the whole water column, from the surface to near the sea floor. The water column makes up 95-99% of livable area on the planet. Nutrient availability in the open ocean is more complicated than in an estuary in part because of depth and currents — there is a lot of dynamic three dimensional space to move through! In the open ocean, most of the interactions between living things happen near the surface where light is available. Then, the nutrients and energy at or near the surface are carried through the water column when the primary producers, mostly phytoplankton, are eaten or die and sink.

Within this environment, phytoplankton are the main primary producers, consumed by zooplankton or krill, which are in turn eaten by small fish, and the fish are eaten by larger predators. Top predators in the open ocean, such as orcas, sharks, and whales, spend their lives traveling large distances in search of enough prey to meet their energy needs and reproduce. This means that in the open ocean, many predators are opportunistic; it's more about who they run into rather than a preference for one species or another. Humans are also a top predator in the open ocean, harvesting large predatory fish including tuna and swordfish.

Learn about pelagic food webs.

Freshwater

Freshwater ecosystems include lakes and rivers. Food and nutrients are often transferred between the aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Amphibians like frogs move between water and land. Insects like mosquitoes, dragonflies, mayflies, and others start their lives as larvae offsite link in the water, eating phytoplankton or zooplankton as lower trophic level consumers, then finish their lives on land. Birds and other terrestrial animals can be top predators in freshwater ecosystems. Leaves and animal carcasses fall into the water and provide food for scavengers and decomposers. Not only are the species in freshwater ecosystems different from their marine counterparts, but the top carnivores tend to be smaller. Top predators tend to be birds, reptiles like alligators, or large fish like trout.

While tracking humpback whale location and movement in an effort to prevent ship strikes in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, researchers discovered something interesting — humpback whales and other predators follow one of their favorite foods.

What is unique about aquatic food webs?

Aquatic food webs are unique for several reasons. One key factor is their connectivity. For example, sharks rely on estuaries and coastal waters as nursery grounds where they reproduce. These areas provide protection and food for young sharks until they are ready to venture into the open ocean themselves in search of larger prey and mates. Similarly, salmon travel through both marine and freshwater ecosystems, feeding a wide range of predators and supporting multiple aquatic ecosystems. The movement of species in and out of different aquatic ecosystems makes these food webs complex, especially with seasonal changes.

The water environment itself adds complexity to aquatic food webs in ways land-based ecosystems cannot. Filter feeders, for example, pull in food from the water around them. Many aquatic organisms reproduce by broadcast spawning, releasing eggs and sperm into the surrounding water in the hopes of creating larvae, some of which feed on plankton as they grow. Filter feeders can eat the eggs, sperm, and larvae, along with their usual plankton diet, all while helping clean the water offsite link. The varying amount of light, oxygen, salinity, and pressure in the ocean all require organisms to develop special adaptations and can create surprising predator-prey interactions, especially in the deep sea. For instance, jellyfish use unique trapping methods offsite link to capture a wide variety of prey, including squid.

Additionally, there are temporary food webs in special aquatic habitats. For example, when a whale dies and its remains sink to the bottom of the ocean where food isn’t as readily available, its carcass becomes a food source for scavengers and decomposers until it is picked clean. Vernal pools offsite link, which are temporary shallow pools of freshwater formed by spring rains, are another example. These mini-wetlands support the existence and reproduction of more than 700 species in the northeastern United States alone. Amphibians such as frogs and salamanders that rely on these pools help control insect populations and in turn feed predators such as snakes and hawks. None of these food webs would be possible without water!

Humans and aquatic food webs

Humans play an important role as one of the top predators in many aquatic food webs. It is our responsibility to ensure that our fisheries are sustainable and that we are not polluting the ocean with toxins that can build up in food webs.

Overfishing of top predators can harm ecosystems similar to how the decline of otters harmed kelp forests. As big as the open ocean is, overfishing top predators like tuna and swordfish can disrupt food webs on a large scale. Regulations are put into place to limit the amount of fish species that can be caught to prevent overfishing to protect ecosystems and ensure there are more fish to catch the following year.

Biomagnification is another major concern in food webs as a result of pollution. For example, heavy metals like mercury can enter the environment because of human activities including burning fossil fuels or human waste, industrial processes, or mining. Bacteria change mercury into a more toxic form known as methylmercury which can build up in the tissues of organisms that eat it. As predators eat other organisms, the mercury in their bodies increases. The process of biomagnification can lead to dangerously high mercury levels in top predators such as tuna and swordfish that are then eaten by humans.

EDUCATION CONNECTION

Education plays an important role in the health of our aquatic food webs. Whether students live inland or on the coasts, their actions affect the health of one of our major food sources. This collection contains a variety of multimedia, lesson plans, data, activities, and information to help students better understand the interconnectedness of food webs and the role of humans in that web.

Glossary

Definitions of some of the terms used in this resource collection.

Biomagnification

The concentration of toxins in an organism resulting from ingesting other plants or animals within which the toxin is widespread.1

Carnivore

Organisms that only eat meat or the flesh of other animals for energy and are either secondary or tertiary consumers.2

Consumer

An organism that gains energy by feeding on other organisms.2

Decomposition

Organic matter is broken down to carbon dioxide and mineral forms of nutrients by organisms such as bacteria and fungi.2

Detritivore

Organisms that primarily eat detritus, or dead or decaying remains.2

Ecological community

A group of organisms that live in the same area at the same time.2

Ecosystem

A system made up of the biological, physical, and chemical components that interact with one another in a given area.3

Herbivore

Consumers that only eat plant life for energy.2

Food chain

Food chains describe who eats whom from the plants at the bottom to the major predators at the top of the food chain.4

Food web

All of the food chains in a single ecosystem connect to show how all animals in an ecological community are connected.2

Omnivore

Organisms that feed at multiple levels of the food web; they eat plants, fungi, and animals for energy.2

Producer

An organism that makes its own food through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis.2, 5

Trophic cascade

The removal or addition of a top predator affects the populations of species at lower trophic levels within a food web. This causes a cascade of changes throughout the whole ecosystem.6

Trophic level

The position of an organism in the food chain, for example, producer, primary consumer, secondary consumer, tertiary consumer.2, 7

Water column

The water between the ocean surface and the sea floor. Specifically, the space that water takes up, or its volume, from the ocean surface to the sea floor.8, 9

Keep exploring

Find even more resources on aquatic food webs in our searchable resource database.